Manila 04 - Agham Rd settlement, adjacent to Phil. Central Bank, Quezon City

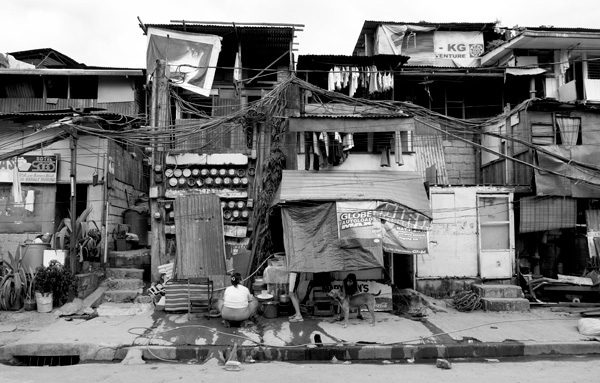

Manila 05 - Bankal settlement with billboards, Makati City

Manila 06 - Morning Commuter train through Bankal settlement, Makati City

These photographs were made over the past five years as part of a survey

of the architecture of informal settlements in Metro Manila. The study had

city planning, architectural and economic components and resulted in the soon

to be published Lungsod Iskwater, The Evolution of Informality as a Dominant

Pattern in Philippine Cities, by Alcazaren, Ferrer and Icamina. The survey

grew out of a comment by the Cuban-American urban planner, Andres Duany, who,

in a lecture about the metropolis, noted that the solutions for Manila’s

myriad urban problems would more likely come from the squatter settlements

than from the exclusive enclaves that Manila’s elite inhabit.

As I made these photographs I was struck by the contrast between the trepidation

that non-squatter residents would express about their neighbors and the whole-hearted

welcome that the settlement residents would greet me with when I asked to

photograph their homes. I came to realize that most of the squatters were

there by choice. More often than not, they paid rent to someone who had connections

with local authorities, were building on tiny plots of untitled, marginally-habitable

land and had made a carefully considered choice to live on the edges of what

was legal and prudent. I found that invariably, they had created communities

that were self-governing and humane, pockets of sanity in a city of three

hour a day commutes through blinding pollution in the chaos that is Metro

Manila.

Informal settlers face the same urban problems as others in the city, of course,

with the added dangers of violent eviction, sweeping fires that can raze entire

communities in minutes, institutionalized crime, and sanitation problems characteristic

of an urban sink. On the other hand, in many communities I visited, shoes

and sandals are left out on the doorstep without fear of theft, and young

children play without danger, supervised by all neighboring adults. I found

that people were highly aware of and genuinely concerned about

their neighbors, expressing a sense of cooperation and tolerance that is often

rare in formal communities. In addition, I found that the architectural solutions

were often surprising in their use of materials and space, often redefining

the limits of human habitation.

It is not my intention to romanticize life in these communities—by any

standard, it is a tough, hand-to-mouth existence every single day: tiny, flimsy,

untitled dwellings constructed of discarded materials, without proper water,

sewage or electrical connections, alongside fetid drainage canals or an arm’s

length away from raging commuter trains. Yet, as we become increasingly aware

of the damage we, as a species, have done to the planet and as the prospects

of long-term human survival dim, I wonder if these photos aren’t an

optimistic glimmer of the future of the human species on earth.

Neal Oshima

October 2006