Both Flather and Dixon printed their images onto albumen paper, the standard printing medium of the period. Both groups of photographs now show signs of fading, Dixon’s more so than Flather’s. In fact, albumen prints could show signs of fading quite soon after being made and there was understandable concern about this. One printing method designed to overcome this problem was the carbon process, introduced in the 1870s. As the printed image is formed of carbon pigment rather than silver it is pretty permanent (the oldest surviving man-made drawings were done thousands of years ago with carbon pigments on cave walls). Dixon mastered this difficult process and, significantly, used it for the next major urban landscape project in which he was involved.

This was a commission from the Society for Photographing Relics of Old London (SPROL), founded in 1873. However, Dixon wasn’t engaged initially by the society, that honour went to Alfred and John Bool. As the name suggests, SPROL was established in response to the redevelopment work that was going on in London and the consequent threat of demolition to a lot of old buildings, some of them pre-dating the Great Fire of 1666. The catalyst which brought the society into being was the proposed demolition of the Oxford Arms in Warwick Lane. This was one of the old galleried coaching inns made redundant by the coming of the railways and was slowly falling into disrepair. However, it symbolised what many, including the founders of the society, thought to be London’s historic past and if it couldn’t itself be saved (the site was needed for the expansion of the Old Bailey next door) then at least a photographic record of it should be made for posterity.

Thus, at the society’s behest, the Bools undertook a series of views of the Oxford Arms and, again, picturing the building in relation to its surroundings was felt to be important. One of most striking images in the seireis is a roof-top view showing the familiar dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral in the background. Over the next 3 years the Bools photographed a number of other historic sites for the society, notably St. Bartholomew’s and Cloth Fair, but their services were replaced by those of Henry Dixon in 1879.

Dixon continued to photograph for SPROL until it disbanded in 1886 and he was also responsible for printing all of the negatives, including those taken by the Bools, for issue to the society’s subscribers. In keeping with the society’s preservationist principles, he printed the photographs in permanent carbon and they survive today in what appears to be perfect condition. Although the original carbon printing process is now defunct, modern technology has brought us a new version in the form of carbon pigment inks for monochrome printing using standard consumer inkjet printers. Prints made with these inks will doubtless outlive any made with the various silver-based printing processes used over the past 165 years.

page 1 Talbot, Fenton and Flather

page 2 Dixon and Bools

page 3 Strudwick

Henry Dixon: panoramic ‘joiner’ of Holborn Viaduct under construction,

1869

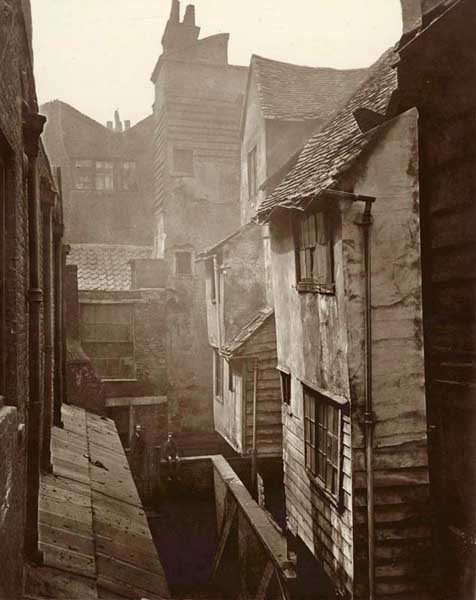

Henry Dixon: The Shambles in Aldgate, 1883 (for SPROL)

Alfred & John Bool: The Oxford Arms from the Old Bailey looking towards

St. Paul’s Cathedral, 1874-5 (for SPROL)

Alfred & John Bool: The Poors’ Churchyard, Cloth Fair, 1877 (for

SPROL)